It was announced yesterday that Tim Geithner, President Obama's first Treasury secretary, will become president of Warburg Pincus, a private-equity firm. Before joining the Obama administration, Geithner had been president of the New York Fed, and before that worked for Bob Rubin in the Clinton Treasury Department. (Rubin, co-chairman of Goldman Sachs before becoming Treasury secretary, advised Clinton to repeal Glass-Steagall and nixed the regulation of derivatives. After leaving the administration Rubin became chairman of Citigroup's executive committee, and was there when Wall Street nearly melted down in 2008; he is now a counselor at investment bank Centerview Partners LLC.) Geithner's move to Wall Street follows Peter Orszag, Obama's first director of the Office of Management and the Budget, also a Rubin protégée, who is now vice chairman of Citigroup's corporate and investment banking group.

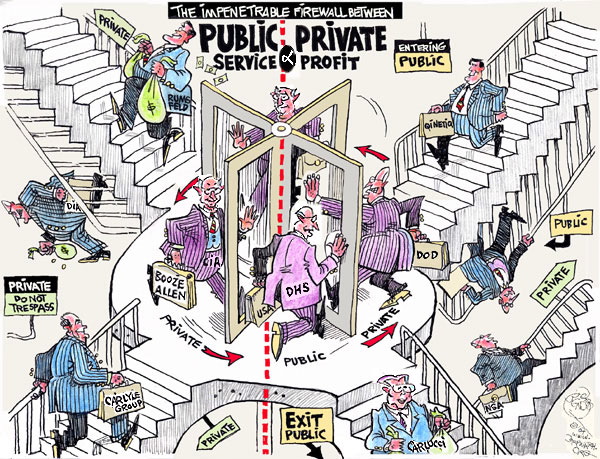

I don't begrudge those public servants who, after leaving office, take high-paying jobs in the private sector. But when someone who has been in charge of bailing out Wall Street and then shepherding through Congress regulations designed to prevent another near collapse, one can't help but worry. The public is already so cynical about both government and Wall Street that even the mere possibility that Geithner knew where he'd be heading afterward, and therefore pulled his punches, can only deepen the cynicism.

Wall Street's political power is a direct result of both the money it pours into political campaigns and the revolving door between it and Washington. So far, Wall Street's biggest banks have fought back tighter regulation (eviscerating much of the Dodd-Frank Act). Private equity has proven even more potent: It has preserved the "carried interest" loophole that allows the pay of private-equity executives to be taxed at low capital-gains rates even though these executives don't risk their own capital. (They buy and sell companies with funds from investors and with debt, typically charging an annual management fee of 2 percent of the funds and keeping 20 percent of the profits as a "carried interest.") During his time at Treasury, Geithner argued for “eliminating the carried interest loophole that allows some to pay capital gains tax rates on what is essentially compensation for services," as he told the Senate budget committee in 2012. One wonders whether he will stand ready to say the same thing again.

--Robert Reich, American political economist, professor, author, and political commentator

Links:

No comments:

Post a Comment